Nearly two years after settling a $1 million avian mortality suit with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) for violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), Duke Energy Renewables says technological advancement and good old-fashioned monitoring have provided valuable insights into the behavior of golden eagles.

Nearly two years after settling a $1 million avian mortality suit with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) for violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), Duke Energy Renewables says technological advancement and good old-fashioned monitoring have provided valuable insights into the behavior of golden eagles.

In 2013, the DOJ brought misdemeanor charges under the MBTA for 14 golden eagle mortalities at Duke Energy's Top of the World Windpower Project and Campbell Hill Windpower Project near Casper, Wyo. Under the settlement, the developer was required to implement an environmental compliance plan aimed at preventing further bird deaths.

Tim Hayes, Duke Energy Renewables' environmental director, says the company – and the wind industry – is a better steward of the environment thanks to its increased monitoring.

For its part, Duke says it had already put in vigorous eagle protection measures in place when the site first began to experience eagle mortalities in 2010, well before the 2013 MBTA settlement.

For starters, Hayes says the company's informed eagle curtailment programs have enabled Duke to observe eagle behaviors. In short, the company knows more than it did even two years ago.

‘We're starting to figure out risky behaviors,’ he explains. As an example, in what is referred to as ‘directional flying’ – from Point A to Point B – there's little risk. ‘However, when the head is tilted down – in hunting mode – that's when (golden eagles) are going to get into trouble.’

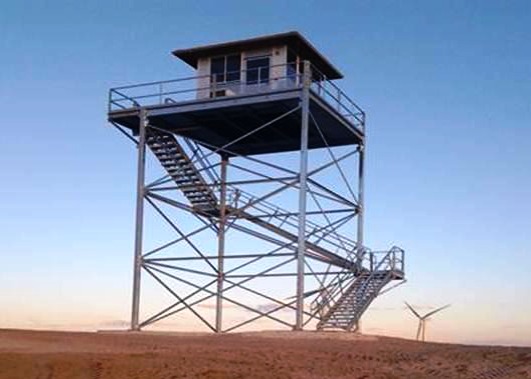

To better protect eagles – and the company itself – Duke constructed a 30-foot observation tower that is staffed by a field biologist monitoring the sky for the presence of golden eagles. If an eagle is in the vicinity, the biologist is empowered to curtail the affected wind turbines from controls located inside the observation tower, a process that takes about six to 10 seconds – a vast improvement from previous procedures where curtailment instructions were flowed through the company's Charlotte, N.C.-based operations center.

A second biologist – in direct radio contact with the observation tower – also monitors the sky from a point on the wind farm that affords a panoramic view.

‘We've shaved minutes off the [curtailment] process from when everything went through the control center in Charlotte,’ Hayes says.

Before the DOJ settlement, Duke also employed a radar surveillance system but scrapped the technology after about six months because the radar technology still needs some fine-tuning for wind farms.

Currently, Duke is in beta testing with a camera detection system that, according to Hayes, carries a lot of potential. The camera scans the sky and picks up an image. ‘Once it meets logorithic criteria for an eagle, our hope is that a signal can be sent to fire an audible or visual deterrent, or curtail the turbine, or both.’Â

‘Of all the things we've looked at, this holds the most promise,’ Hayes says. ‘It's another set of eyes in the sky.’

He says the combination of field biologists, the radar surveillance and camera detection system have generated reams of data on eagle behavior that Duke plans to share with the wind industry.

Finding a silver lining, Hayes says that the DOJ settlement has allowed the company to be completely transparent – meaning it can share best practices and lessons learned with others, such as PacifiCorp, which also pleaded guilty to violations of the MBTA in 2014.

Although several variables can make it difficult to declare such a blanket statement, Hayes is nonetheless certain the company's efforts are working.

‘I'm confident that we are saving eagles.’

Caption: Duke's 30-foot observation tower in Wyoming is equipped with controls to curtail wind turbines if golden eagles are present.