A new study from Bat Conversation International claims that wind turbines may be threatening the survival of one of North America’s most widespread migratory bats, the hoary bat.

According to the nonprofit group’s study, published in Biological Conservation, the hoary bat, Lasiurus cinereus, is the bat species most frequently killed by wind turbines in the U.S. and Canada. Although they’re currently widespread across the continent’s forests, an estimated 128,000 are killed each year, the group says.

The group adds that its research is the first of its kind to reveal how these fatalities may directly cause dire impacts on a whole population and future of a bat species.

“The hoary bat could be the next spotted owl. This species is headed for the emergency room if we don’t act now,” says Mike Daulton, executive director of Bat Conservation International.

The study – which the group says brought together international experts, academics and biologists from several federal agencies – looked at hoary bat mortality at wind energy facilities. It revealed that populations of the species may plunge by a staggering 90% over the next 50 years if no action is taken to curb the bat mortality.

“These findings are a wakeup call. Our study focused on the hoary bat, which has the highest observed fatalities,” says Winifred Frick, senior director of conservation science for Bat Conservation International and lead author on the paper. “Other migratory bats also have high levels of mortality from wind turbines.

“We need to implement significant conservation measures to reduce mortality from wind turbine collisions – and soon. Effective conservation measures will help not just hoary bats but all bats that get killed by turbines.”

However, Daulton adds, “Solutions are within our grasp. We have great hope that this is a problem that the conservation community, key government agencies and the wind industry can work together to solve.”

The American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) has issued a statement in response to the study.

“The wind industry is confident that the conservation measures we have put in place and those in the pipeline can prevent the scenario articulated in this study,” says Tom Vinson, vice president of federal regulatory affairs at AWEA. “These conservation measures were not considered by the authors.

“The wind energy industry takes its wildlife conservation responsibilities seriously, including with respect to bats, and is proactively working to reduce our impacts. Even for bats that are not protected by federal law, the industry conducts pre-construction studies to understand potential risks and develops bat conservation strategies to address any concerns. That includes provisions to implement additional conservation measures if issues arise and monitoring at operating facilities to verify actual impacts,” he says.

Vinson points out that the wind energy industry also has in place a “voluntary best-management practice that limits the operations of turbines in low-wind-speed conditions during the fall bat migration season,” when there is the highest risk of collision.

He says the industry is also “supporting research to improve our understanding of these issues and options to reduce impacts.”

“Early results of the research into acoustic deterrent devices – for example, using ultrasonic sounds that bats can detect to ward them away from turbines – have shown promise, and that research continues,” he explains.

Notably, Vinson points out that many bat species are being harmed by white nose syndrome and are “at further risk as a result of climate change, for which expanding wind energy is a leading solution.”

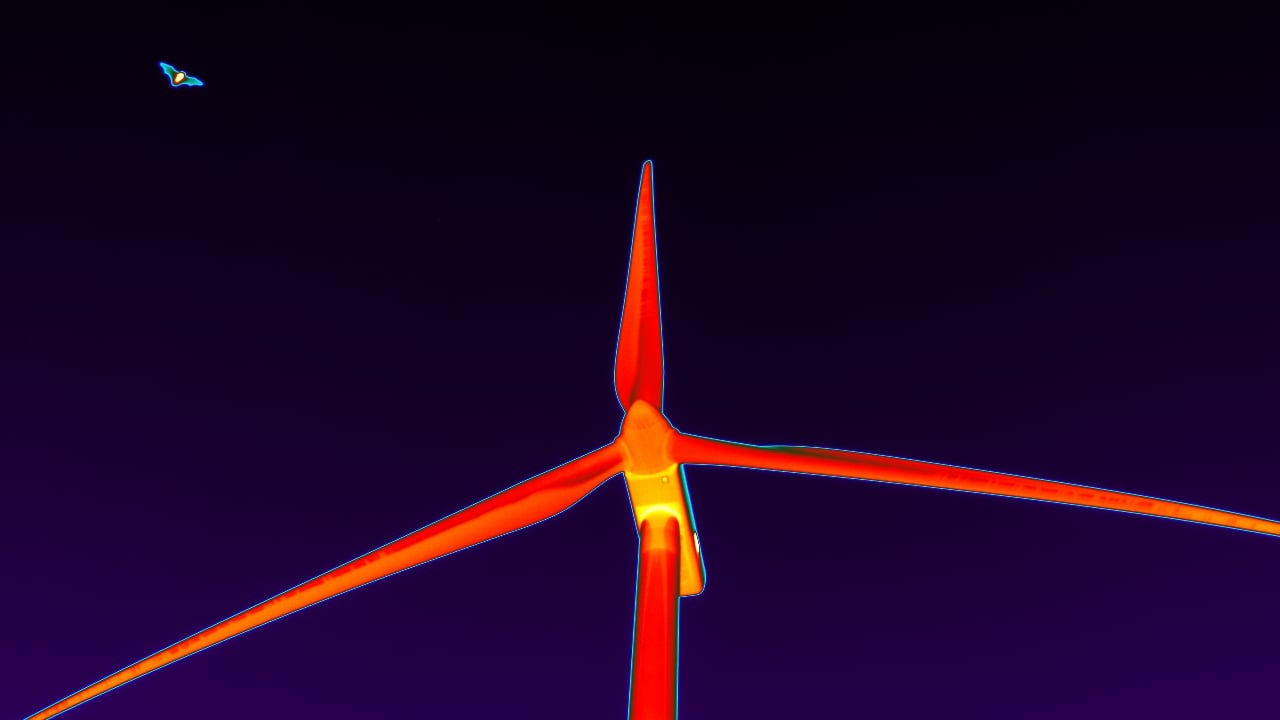

“The wind industry has a legacy of care for the environment and will continue to work to protect bats while addressing these larger threats to their survival,” he concludes.  Photos courtesy of Michael Schirmacher of Bat Conservation International

Photos courtesy of Michael Schirmacher of Bat Conservation International

To the Editor at “North American Windpower”.. The Hoary Bat is the latest flying animal on our planet to be identified as threatened by the prosaic horizontal axis wind turbines that are known in daytime and nighttime hours to slice and dice birds. In the Altamont Pass windfarm the poor solution to the large numbers of raptors killed on a daily basis, such as Peregrine Falcons, Bald Eagles, Golden Eagles, and Redtail Hawks, was to remove certain turbines in high mortality flyways. The turbines removals lessened the mortality rate but hardly was a solution for a turbine technology that inherently… Read more »