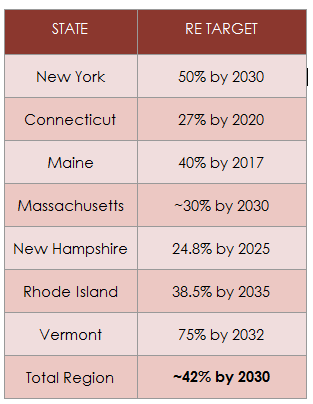

The Trump administration’s rollback of federal climate and clean energy policy has relegated renewable energy development to states (for at least the next four years). Northeast states are among the leaders – New England and New York together target 42% renewable generation by 2030, which is more than double the 20% installed capacity they had in 2015 – but states across this region are also some of the most land-constrained regions in America.

Even though Northeastern states have ambitious renewable energy goals, will barriers to siting new wind generation and transmission in a land-constrained region stymie their efforts? A new research paper from America’s Power Plan (APP), “Siting Renewable Generation: The Northeast Perspective,” seeks to answer this question by combining existing siting policy work and proposing new approaches to siting renewable energy and the transmission necessary to get it to market.

The most ambitious regional goals, the most constrained lands

The seven Northeastern U.S. states participating in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) complement their binding emissions-reduction goals with renewable energy standards. These targets will drive the region to at least 42% renewable energy by 2030, most likely from wind and solar.

Such a tremendous build-out of wind and solar in a relatively short time presents major hurdles for a region where many potential locations are blocked by private or preserved land. Unfortunately, states have not yet identified ideal sites for wind, solar and  transmission, though renewable energy goals are on their books.

transmission, though renewable energy goals are on their books.

Consider New York State, which established an ambitious 50% by 2030 renewable generation goal in 2016. In order to achieve this goal, the New York Public Service Commission estimated the state would need 3.5 GW of onshore wind and 6.8 GW of utility-scale solar – requiring approximately 700 square kilometers to site the wind turbines and 136 square kilometers to site the solar panels (according to National Renewable Energy Laboratory land-use estimates).

New York’s goal depends on whether projects will get timely regulatory approvals and permits, as well as if private landowners are willing to open their property to development, but the state’s history of delays and defeats in siting new renewables haunts investors. According to the Alliance for Clean Energy-New York’s executive director, developers estimate the best-case scenario for building a new wind farm is four years, but obtaining permits and overcoming opposition can take up to eight.

The challenge facing onshore wind

Developers have had mixed success siting wind farms across the region. Farming communities are often supportive due to substantial lease fees and tax benefits while turbine spacing leaves room for all but the largest farm equipment, but homeowner and environmental opposition can often prove intractable.

Local zoning regulations have often been used to circumvent state certification processes and can delay, if not ultimately prevent, the licensing of new wind farms. For instance, several towns in New York have adopted six-month moratoriums on siting wind turbines and the meteorological towers needed to assess wind resources – indirectly nullifying state authority to site utility-scale generation necessary for its renewable energy goal.

This local opposition indicates a larger legitimate concern, and without addressing it, state and local siting preemption can unnecessarily overlook solutions capable of siting needed infrastructure without burdening local communities. Because local communities often lack ordinances dealing with wind turbine siting, the scramble to respond when a new project is proposed often leaves local action open to the most vocal opponents. To alleviate this problem, APP recommends local governments in areas suitable for wind development create ordinances dealing with siting before projects are proposed.

Offshore wind’s role moving forward

In addition to preemptive local government policy, APP sees a larger role for offshore wind to play in reaching the northeast U.S.’ renewable energy goals. Though Massachusetts’ experience with Cape Wind stands as a warning that offshore wind is not immune from siting challenges, new projects are faring better, thanks to supporting state siting policies and increasing developer sophistication.

For instance, the Massachusetts Act Relative to Energy Diversity supports offshore wind development and reduces risks for developers by carving out special areas for projects and requiring utilities to contract for 1.6 GW of new offshore wind. In New York, the state’s Offshore Wind Blueprint and Offshore Wind Master Plan support new projects through stakeholder input and environmental studies.

In addition, state or regional transmission plans minimizing siting conflicts for offshore wind can drive new project development. Similar to the Atlantic Wind Connection effort, organizing coastal interconnections and undersea transmission networks can lead to faster, more environmentally friendly and cheaper approaches to link offshore wind farms with onshore load centers – often at previously developed industrial areas along the coast.

Making the most of existing transmission and underutilized land

The APP research also recommends making better use of existing transmission capacity to facilitate new wind generation. As conventional fuel-based generation retires for environmental and economic reasons, new wind can tap the grid infrastructure left behind. The paper highlights existing substations and interconnection points currently servicing large, retiring coastal nuclear or coal plants as potential low-conflict terminals for offshore wind electricity.

In addition, the paper suggests that resource-planning processes prioritize locations for wind generation that complement other renewable resources on the system – for instance, matching wind variability against imported Canadian hydro to optimize grid capacity. Distribution operators ought not forget about distributed wind, as well; substantial leasing revenue can make renewable development attractive to farmers in northern areas of the region where wind is plentiful but compatible land is sparse.

Finally, APP suggests wind developers and policymakers consider land trust or other conserved properties to site new generation. One approach under consideration in New York State is encouraging local land trusts to review their inventories and aid in identifying suitable sites for wind turbines while designing new conservation easements to include wind energy.

Both from America’s Power Plan, Mike O’Boyle is the power sector transformation expert for energy innovation, and Eleanor Stein is a former administrative law judge for the New York Public Service Commission and a former project manager at New York’s Reforming the Energy Vision. America’s Power Plan brings together clean energy stakeholders to assemble information on policies, markets and regulations to maximize the grid’s affordability, reliability/resilience and environmental performance.