A combination of surging electricity demand, sinking technology costs and innovative policymaking has allowed developing nations to seize the mantle of global clean energy leadership from wealthier countries, a comprehensive new study from BloombergNEF (BNEF) concludes.

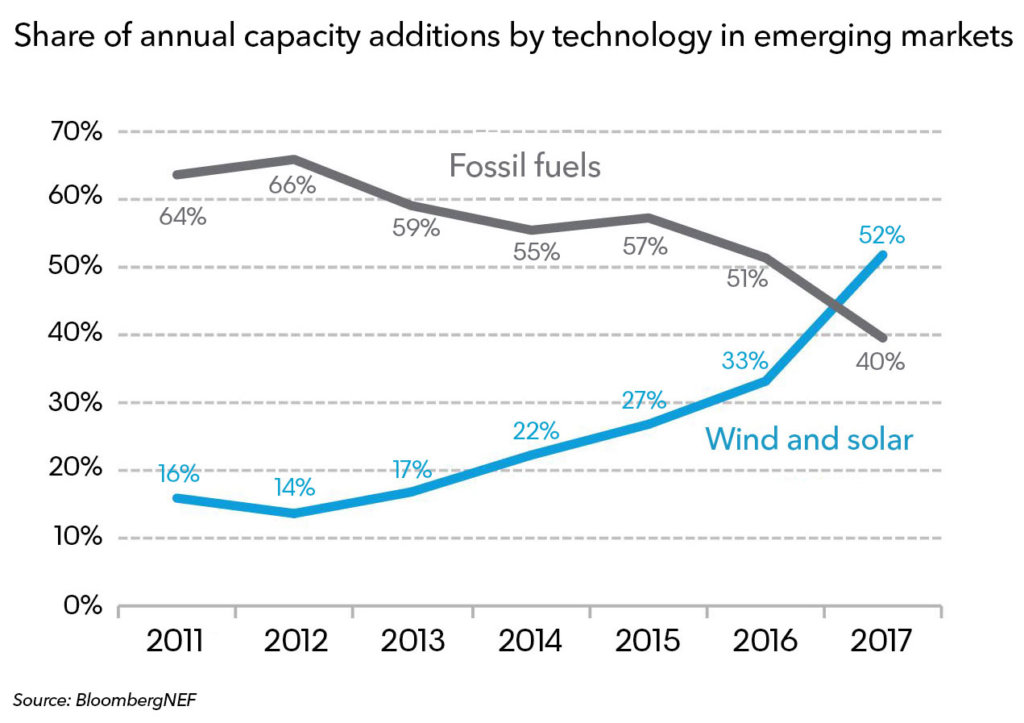

Between them, emerging market nations surveyed by BNEF’s annual Climatescope project accounted for the majorities of new clean energy capacity added and new funds deployed globally in 2017. These countries are also playing the leading role in driving down clean energy costs so that energy access can be expanded without boosting CO2 emissions, the report says.

In 2017, developing nations added 114 GW of zero-carbon generating capacity of all types (including nuclear, large hydro and other renewables), with 94 GW of wind and solar generating capacity alone – both all-time records, according to BNEF.

Concurrently, they brought online the least new coal-fired power generating capacity since at least 2006, the report says. Moreover, new coal build in 2017 fell 38% year-on-year to 48 GW; that represents half of what was added in 2015, when the market peaked at 97 GW of coal commissioned.

“It’s been quite a turn-around. Just a few years ago, some argued that less developed nations could not, or even should not, expand power generation with zero-carbon sources because these were too expensive,” says Dario Traum, BNEF’s senior associate and Climatescope project manager. “Today, these countries are leading the charge when it comes to deployment, investment, policy innovation and cost reductions.”

According to BNEF, this shift is being driven by the rapidly improving economics of clean energy technologies – most notably, wind and solar. Thanks to exceptional natural resources in many developing countries and dramatically lower equipment costs, new renewables projects now regularly outcompete new fossil plants on price – without the benefit of subsidies, the report says. This has been most apparent in the more than 28 GW contracted through tenders in emerging markets in 2017, involving promises from developers to deliver wind for as low as $17.7/MWh and solar for as little as $18.9/MWh.

Climatescope also revealed that clean energy dollars are flowing to more nations than ever. As of year-end 2017, some 54 developing countries had recorded investment in at least one utility-scale wind farm, and 76 countries had received financing for solar projects of 1.5 MW or larger. That’s up from 20 and three, respectively, a decade ago, BNEF reports.

Development banks, export credit agencies and other traditional backers of projects in emerging markets continue to play an important role in the clean energy build-out. But private players – most notably, international utility companies – are now among the top investors, as well, according to the report.

“European players, in particular, have moved aggressively to finance projects, particularly in Latin America,” says BNEF’s head of Americas, Ethan Zindler, who helped found Climatescope. “While concessional capital is still clearly required in least developed countries or in others just beginning to adopt clean energy, elsewhere, private funders appear quite comfortable deploying capital at volume.”

Climatescope 2018 represents the collective effort of 42 BloombergNEF analysts visiting 54 countries to collect data and conduct interviews. As in years past, the study was underwritten by the U.K. Department for International Development. For 2018, the project was expanded to survey 100 nations classified by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development as less developed, plus Chile, Mexico and Turkey, which represent important clean energy markets, notes BNEF.

Climatescope includes a scoring system for measuring how conducive nations are to clean power investment and deployment.

In the current survey, Chile was the top scorer. The Andean nation fared well on all three main topic areas Climatescope surveyed, due to strong government policies, a demonstrated track record of clean energy investment, and a commitment to de-carbonization despite grid constraints. India, Jordan, Brazil and Rwanda ranked second through fifth, respectively. China, which received the highest score in the survey last year, finished seventh.

Despite successes achieved by clean energy to date in developing countries, Climatescope included sobering findings about the scale of the challenge ahead, BNEF points out. While new coal-fired capacity additions fell to their lowest level in over a decade in 2017, actual generation from coal-fired plants rose 4% year-on-year to 6.4 TWh. And despite ample evidence that new-build renewables can underprice new-build coal-fired plants, 193 GW of coal is currently under construction in developing nations today. Some 86% of this capacity is due online in China, India, Indonesia and South Africa.

In the context of keeping global CO2 emissions in check, the longer-term challenge for clean power is not just to beat out new coal-fired power plants for new-build opportunities, according to BNEF. Rather, it is to displace existing coal-fired plants, many of which have just recently come online.

China and India get approximately two-thirds and three-quarters of their current power from coal, respectively. Combined, these two countries added 432 GW of coal capacity in just the 2010-2017 period. (By comparison, the U.S. has a total of 260 GW of coal online today). Faced with significant pressure to expand energy access in India and keep power affordably priced in China, policymakers will be reluctant to decommission these new plants, says BNEF. No less than 81% of all emerging market coal-fired capacity is located in these two nations alone.

Finally, Climatescope highlighted growing challenges associated with integrating large volumes of variable resources into existing power markets and the role they can play in depressing wholesale power prices. Further growth will require a variety of solutions, including expanded transmission capacity, demand response programs and power storage technologies, the report concludes.